To give birth, you must dive headfirst into the great mystery. Your body transforms, a new being

emerges, life is never again the same. But we can’t say how it will happen. And if we have questions

later, we may never know why things went the way they did. Yet the experience remains, etched onto

ourselves, whispering through every slackened muscle fiber and weakened ligament. Our wavering

connective tissue thinning with every strain, connecting past with the present. Is there any experience more

visceral? This is the story of my second child. A redemptive birth fraught nonetheless with the

cognitive dissonance of empowerment and helplessness. I wanted a VBAC, and so to tell the story of

the second I must first review the first.

My first birth was lengthy and typical of what is sometimes called “the cascade of interventions”. I had

several ineffective sweeps starting as early as recommended and eventually opted for a castor-oil

induction at 9 days past due. The midwife who suggested it never told me that any form of induction

increases one’s risk of c-section. My water broke early, with meconium in the fluid. Arriving at the

hospital my labour was heavily augmented and I did not think to question it. I rode the waves beyond

the pale until the dial on the synthetic oxytocin drip was nearly maxed. The epidural was not suggested

by myself, but I accepted once it was offered. Throughout we saw decels, decels, big decels. I endured

nearly every test there was to confirm the infant was healthy and did not need the cesarean birth that

was being repeatedly recommended. I shouted at the resident to stop hurting me with the stupid cone

they test with, and I even let them stick the wire in baby’s in-utero head to monitor his pulse adequately

(he still has one hair that grows in a corkscrew out of the tiny scar that remains). I felt like I was

hooked up to every kind of cable but the internet. I was only given hospital juice and popsicles to eat.

After about a day of this, and after one particularly big decel, I was actually fully dilated. The

condescending obstetrician gave me the option to try and push the baby out in an hour. Exhausted after

a day of eating only popsicles and juice, and fearing I would not be able to perform this final feat, I

chose not to. Instead, I submitted to a c-section I now regret, although I can accept that my partner and I

thought it seemed like a good idea at the time. No one informed me that pushing, even if it ended in

surgery, would improve my chances of having a vaginal birth with subsequent children. My son

ultimately arrived 10 days past due in the OR. My doula told me I was the best hypnobirther she had

ever seen, and I don’t think she was having me on. My lanky son was born with the cord around his

neck and a hand beside his head; I imagine a vaginal birth would not have been optimal, although there

is plenty of facts out there to suggest that this is not actually true. I’m told the OB on at that point was a

rock star surgeon. She told me that “he was just too big for you, dear”, a statement I consider to be

highly debatable and basically untrue. 3 years later my scar sure looked good, so thin and white and

even that every healthcare practitioner who saw it remarked on its flawlessness.

This time would be different. I knew more, I cared more, I believed. No risk factors for VBAC other

than my propensity to gestate statistically large humans, and never having pushed the first time around.

To believe and to try to take great strength. To surrender and accept take yet more. I have done all this and

then some.

October 14, 2015, 9:00am (because dates and times underline the birth experience, for we must know if

we are “normal”, “regular”, “average”, “safe”. Let us temper our intutition with statistics and tell

ourselves we made the Best. Possible. Decision. This is the double-edged sword of informed consent,

where you have a say in compromising your destiny.). As with my first birth, I was 9 days past due and

desperately wanted to do something about it. A week and a half is obviously my natural threshold of

waiting. Now I was finally ready to accept a sweep; unlike the first time I had held off until now,

convinced of their non-necessity. I texted Andrea, my midwife, and made an appointment for 1:00pm at

the clinic.

That Tuesday morning my body was clearly readying. Flickering tensions of several days were rising to

become the occasional recognizable wave. I sent my 3-year-old son out with my husband and made

beef stew to pass the time, knowing it would be eaten later one way or another. I had a significant

contraction while waiting outside for my dear friend Leah to pick me up and take me to the clinic.

Although not acting as mine, Leah is a midwife. She was going to be at the birth to support me as

a witness, as a friend, outside of the other birth professions. At Andrea’s office, the sweep was easy and I

was probably 3cm gone. A great place to start. We said goodbye and went to a cafe, savouring what I

knew were dwindling hours of peace before starting the next chapter.

On the way home in Leah’s car, I swirled the remaining ice left over from my rooibos tea and chewed

on the straw. The enduring light discomfort from the sweep turned to episodes of distinct pinching as

my body’s gears engaged. Maybe this really was going to happen today. I closed my eyes, breathed

deep, rubbed condensation from the plastic cup. Still unsure, I hedged my bets.

The pinching endured. I greeted my husband and son at home, told them I was excited and it really

would happen soon. Contractions were happening regularly, bringing me to hands and knees on my

living room floor. I texted Leah, told her I was getting in the bathtub to see what happened. Asked her

to get ready to come on my mark. In the bathtub waves kept coming, soon regularly 4-5 minutes apart,

so I texted everyone to come, must have been near 3:00pm. Leah arrived first, comforted me and

cheered me on, started laying tarps and setting up the birth pool. Morag, my doula arrived next, after

picking up her son from school and driving across town. I got out of the tub, tried the TENS machine

for a while. Andrea the midwife arrived. Somehow I got across the house and into the birth pool.

A welcome relief to be floating deep. Knees on the floor and arms over the edge, I roared like a lioness

again and again. Crushing the gentle hands of my caregivers. Drinking. Refusing food. Vomiting.

Living raw power. I dilated quickly and easily surrounded by caring women and flickering candlelight.

Cora, the second midwife was summoned. Rearing up on my knees, possibly standing, Morag

encouraged me to feel the pressure. I touched the veined sac of waters bulging within, the caul

separating dark from light, sustaining the human amphibious. The waters broke. Blessedly clear, the

liquid in the birth pool simply more saline but otherwise unmarked. Things were going so well that by

7:00pm Morag optimistically texted her husband that she might be home for dinner.

And I pushed. Progress made, I felt the child’s head. Touched the hair that had remained secret, hidden

from me for these 9 months. In this moment, I felt like an absolute champion. I was encouraged, I was

strong, I believed. But the going slowed. An internal exam to check for hidden obstacles, none found.

After an hour I needed a break, flipped on my back and reclined in the pool. Everybody told me this

was not a good way to get the baby out. I rejected them: this was my place to rest. Another surge came and

I felt it, a distinct set of parallel lines move within, aligned with my hips, a dramatic sensation that in

hindsight must have been baby’s shoulders. Then a heart rate slowed down, maybe baby’s, more likely

mine. It was time to move.

Up into the arms of women, out of the pool, on to the floor. Groaning on a towel. Heart rate check.

Pushing on the birth stool, on the toilet, on the floor again, in the pool again. Turning my insides out.

Directing every ounce of power into the place of movement, only to be denied again and again. A

desire to quit, to go to the hospital, let someone else take care of it, only to be reminded by my wise

sisters that what I wanted was unlikely to be found there and more time at home was still possible.

Morag suggested a move to the bed. Hospital-style pushing, perhaps warranted here. Staggering,

guided down the hall to a new surround. The bed. On hands and knees, then on my back like an

overturned beetle. Two women supported my legs, the midwife cradled the baby’s head and encouraged

my pelvis, and I gave it my all. Flesh unyeilding, stubborn child, bony spines, cryptic sensations. This

was not the way it would happen.

This time the midwife concurred, it was time to go. Scrambling for the hospital bag, calling caregivers

for my son, getting a nightgown, robe and shoes on, arranging who would drive and who would care

for me on the trip. In that moment I felt no fear or apprehension, my desire to outlive the Sisipheyan

experience was so strong. But writing about it now, I cry. Grieving at the confirmation that the child

would not be born at home, fearing for myself after the fact. Nearing the thin line of having pushed too

long, fearing how I would be treated in the hospital, wondering if I would have surgery again, every

cell clinging to its mortality and clawing against the spectre of morbidity. Not that I nor my child was at

all close to death, but to struggle through the passage of delivering a child, we may remember the

laboured deaths of every mortal mother and infant who came before us. Their flesh is at once ours,

compelling us to endure, to be safe.

After 3 hours pushing at home, it was now 10:00 at night, my son still awake due to my hours of

roaring. Leah stayed with him and told him a story while he fell asleep in the quiet wake of our

departure. She ushered in the grandparents and left to join us at the hospital, writing him a note that she

would finish the story next time she saw him.

Into Morag’s minivan, driving in the dark. Streetlights and intersections, not much traffic, dear goddess

are we there yet. Parking lot, sliding doors, hospital wheelchair. Registration. Resident OB, Evelyn

Somebody. Someone filled in the details for hospital staff; it sure wasn’t me. Hating on the nitrous, it

separated me from the part of myself that focused on coping. Enduring every seemingly useless

contraction I screamed and screamed some more. Crushing the doula’s hand.

Blessed is the epidural when it is truly needed. I think the anesthesiologist tried twice. Determined to

get it right, noting my slight scoliosis. Is this enduring osteopathic curve why the baby wouldn’t turn in

utero, why my spines would not separate to release her? Relief at last. But now was the time to make a

plan. Based on my previous experience giving birth at the hospital I assumed I would be flagged for

cesarean immediately upon entry. A VBAC attempt pushing at home for 3 hours is already well outside

a conventional obstetrician’s realm of comfort. But my preconceptions were not to be affirmed. The

resident agreed I still had a chance of a vaginal birth and she would help try to turn the child. I

questioned her on how many times she had done this. Satisfied with her answer of 50 or so I consented.

And dear Evelyn did try, as did I. Curling, bending, squatting, lying, everyone cheered for me and

helped me along. Feeling a thin line of pain creep across my old scar I resigned before my allotted hour

was up. It was time to consent to surgery.

In me, major surgery evokes the fear of death. To be sliced apart, however beneficial, seems so wrong.

For the knife to come so close to my precious organs and not pierce seems impossible. There is a

reason I am not a surgeon, and I am grateful to the people who are.

Once you decide to go ahead with surgery there is a fair amount of waiting. I called my parents to

update them, tell them the baby was stuck and I was having another cesarean. On the surface I was

asking for their well wishes. Inside I was saying goodbye, just in case.

Another hurdle to overcome was my phobia of cutting. During movies I have to close my eyes when

razors get waved around, when knives and scalpels get held up. I get a fluttering sensation along my

perineum and would probably black out if I followed the sensation to its natural conclusion. I attribute

this to having family members with mental health issues that have led them to self harm. Their cuts are

etched on my memory and my traumatized revulsion is one step beyond that of the average person. So

to have a surgery where I am cut open and expected to remain awake is a tall order. I did consider

having general anaesthetic, but then I wouldn’t get to bond with my child immediately after birth. We

all must make sacrifices.

And so I compromised. As with my first birth I asked for anti-anxiety medication. This was in my birth

plan in the event of c-section for both births and was truly non-negotiable. While I’ve not had cause to

medicate anxiety in my normal life, this circumstance was by definition exceptional, and I am glad to

have had the option.

Goodbye to the labouring room, transported into the elevator, mechanical gurney parts closing and

clanging and wheeling along. Into the OR. Everyone scrubbed up and netted and masked. So many

people reduced to glasses and eyes, frown lines and crow’s feet. Eyebrows. The midwife, my husband,

my friend, the surgeon, the anaesthesiologist and a handful of nurses. Sadly I had to leave the doula

behind; you only get to take so many people in with you, and I had to choose between her or Leah. A

friend of 14 years who has had a c-section herself, who knows me and could witness for me, Leah was

indispensable. My lower half dissapeared under a tent and a vigorous iodine swab was undertaken.

Bright lights. Fentanyl administered. Prick after prick. Overwhelming apprehension. “I feel

something”. “I still feel something”. “Am I supposed to feel something?”. Finally, I felt nothing.

I also really did not want to know what was happening. My birth plan noted that I didn’t want the

surgical team to loudly discuss what they were doing. Some people might have found this interesting or

helpful, but I wanted to hide in my opaque and fuzzy bubble until I got to meet my child. They honored

my request at first. Leah talking to me the whole time, holding my gaze, keeping my mind at bay.

I had the shakes pretty much the whole time. Unlike my first birth where I lay still, even sleeping on

the table at times, now I could not control my arms. Tremors raced through my exhausted body. I

attempted to pin my hands to my chest and focused inwards to reduce the trembling. Finally a nurse

warned “a little pressure,” signaling that the baby was about to be born. My first child had been so high

up inside that the pressure of delivery felt like I was being given the heimlich maneouver; this time the

sensation was negligible, or my nerves were so shot I couldn’t feel it. My flesh rent asunder, mercifully

hidden to my eyes. Our two bodies coaxed apart.

Suddenly there was my baby. At 4:04am, levitated above the tent by a pair of gloved hands, everyone’s

breath held while my exhausted husband figured out and announced that we had a daughter. “Alice!” I

said. As with my first child we had not bothered to find out the sex in utero, but had only settled on one

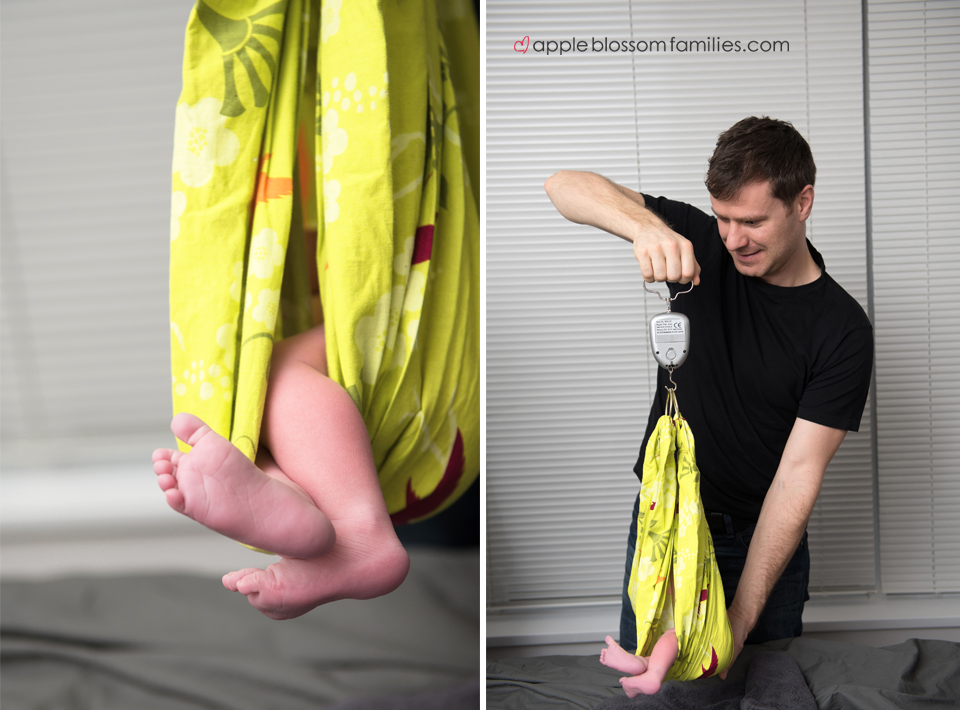

name. Leah asked me how big I thought she was. While I had no idea, she correctly guessed 9lbs 12oz.

My husband stayed with Alice and spoke to her during the initial exam and then she was brought to me

to nurse as soon as possible, as I had requested. Even while I was still on the operating table she was

adept at feeding, and we all marvelled at her audible swallows. As my helpers attempted to reposition

her more comfortably on my chest they were told by a surgical nurse not to push the baby under the

drape so much, as my uterus was still out, sitting on top of me, waiting to be reunited. Indeed, for much

of the time I had been feeling things land on my torso: surgical instruments, my own organs, the hands

of others, but I could not see them and they remained imaginary. To know that my guts were outside of

my body and being handled by others was a truly surreal experience. I understood, of course, but I

didn’t need to hear it. In that moment I appreciated the depth of my numbness.

Eyes Open

Gradually I began to realize that something was going different from my first c-section. I assumed the

surgical team simply had their own working style. But this was taking a lot longer. Alice drank and

drank with Leah or Andrea or Graeme holding her when I couldn’t because of my weak and shaking

arms. Why was this taking so long? Eventually the OB said he had something to discuss. “Give it your

best shot” I said, unbelieving that I was in a state to discuss anything. “OK” he said “I’ll give it the old

college try”. Heh heh, so funny. His masked face rising above the sacred tent he asked if I planned on

having any more children, explaining that I had a large abdominal separation. If I was done

childbearing he could conveniently and generously sew my abs back together. At the time I wanted to

keep my options open for more children; indeed, this was a major factor in why I opted to try for a

VBAC in the first place, as each successive cesarean becomes more risky and difficult. I politely

declined. He then went on to explain that by the time he had cut me open my uterine wall was paper

thin and had torn while I was on the table. I had lost a lot of blood due to the lengthy tear and would

likely need a transfusion. My uretor, the thing that drains waste from my kidneys, had possibly torn in

the process and I would need a CT scan to diagnose. Finally he declared that if I want to have another

child I am strongly advised to plan a cesarean and avoid any natural labor.

Shocking news, cushioned only by my vigorous infant and a haze of meds and exhaustion. And so I lay

there until they were done. Leah stayed with us until I made it to the recovery room, 6:30 or 7am,

despite having somewhere to be at 9am: a true kindness. Graeme called my parents to update them on

my status, celebrating Alice and carefully explaining my injuries. Many jabs and pokes to draw blood.

Was my large infant gestationally diabetic? Nope, just a long history of predecessors who also sprang

into the world at 9lbs plus. Did I need a blood transfusion? No, apparently I had just enough juice left

to sustain myself.

Out of recovery, up to the room. All the while asking “can I have a private room?” and hearing that the

hospital was busy with a bumper crop. Privacy was not to be and we were tucked into the front part of a

hot and stuffy room shared with another family who had clearly endured a difficult vacuum birth; one

overhears everything through that curtain. I’m sure they heard me groaning as the nurses rolled me off

the gurney’s inflatable pad on to the legit hospital bed where I was to spend the next 3 days. I’m sure

they heard me crying heartbroken in the middle of the night, missing my son at home and coming to

grips with the idea that I never ever wanted another cesarean and therefore Alice would be my last

child. Graeme dozing restlessly on a pallet on the floor, lucky to be granted a pillow, wedged between

the cupboard, chair and hospital bed. IV and catheter tubes hanging and dripping, baby tucked into bed

with sleepy me against the advice of the nurses.

After major surgery you only get to sleep a couple of hours here and there. The well-meaning nurses

wake you seemingly continuously, in a form of benevolent torture, to check your vitals and those of

your baby, give you meds, shoot you up with heparin. Then when the sun rises they badger you to

wiggle your toes, to sit up, to try and walk – even though you feel so grim and ghoulish after having

been temporarily eviscerated – so that you don’t get a blood clot and fucking die. And then the doctors

make the rounds. OB, anaesthesiologist, pediatrician. And your blessed midwives come to check on

you, lend you their lip balm, assure you your guts aren’t broken, set the nurses straight, calm your fears

and hug you. The caterers come by with some unpleasant clear fluids and edible gel you devour, and

someone tries to sell you a deal on parking, photography, teddy bears, and TV as though you could

possibly give a shit. And there’s your newborn, cooing and cuteing, wailing and ralphing and nursing

and having a rash and glowing through all of it.

My family came to bring me solid food once I was allowed, scrambled eggs and brown rice and salad,

what could be better? They held the child, gave my husband a break. Helped move the rolling trays

around so that I could get my cold tea in the plastic cup, my phone, my little yogurt left from the

breakfast delivery.

Now, what about this CT scan? Confused nurses saying they don’t have a scanner in the hospital, they

might have to send me to Vancouver General for that. How? In an ambulance or something?

Inconceivable. However, they were set straight by the OB and I got to have my CT at the adjoining

Children’s Hospital.

I highly recommend that if you’ve ever been through a traumatic event that you get a CT scan at

Children’s. At first I was terribly lonely. I had to leave the baby with Graeme and get hefted into a

wheelchair, then get steered down a series of back hallways by a cheerful orderly who was skilled in

the art of conversing with himself, all while dragging my IV pole along for the ride. Now in the other

hospital, I was parked alone outside the scanning room until it was my time. I had been swarmed with

people for the last day and a half while I triumphed and struggled and endured, but now I was suddenly

alone. And feeling very fragile and in pain. Sitting up with my new incision and wondering if maybe I

should have taken that Gravol they offered me in case the contrast dye for the CT doesn’t agree with

me. Suddenly terrified at the thought of puking and rending my stitches I delayed the whole thing for

another 20 minutes while they kindly fetched a nurse back from Women’s Hospital to give me the

meds.

A stone-age nurse had been urging me to “pump and dump” after the CT scan, saying that the

radioactive dye given to me would be bad for the newborn. Thankfully I took up the issue with the

radiologist, and was satisfied that this was unnecessary. I was not about to let an ill-informed nursing

staff make me throw away colostrum, which is one of the more valuable substances on Earth and

supports optimal human development during the newborn stage. One small hurdle of many overcome.

After talking to the radiologist at least 3 people attended to me for the scan. Seeing me morosely

slumped in the wheelchair and leaking the odd tear the tech explained his wife had 3 c-sections and he

understood some of what I was going through. They dripped the weird dye into me and waited patiently

to make sure no ill-effects were felt, then they somehow got me up on the scanning bed. All alone,

without my newborn who made all the bad things fade away into the background, numb and pained at

the same time, lying on my back with medical people hovering over me, part of me was transported

back to the OR. The tears became heavier and all of a sudden I was trembling uncontrollably as I had

been for the surgery. Everyone was so compassionate. They were already staying late as I was their last

patient of the day, not even a child, and here I was shaking during a procedure that required stillness.

As the shaking worsened and slight panic crept in at my inability to regain control, this team worked

their magic. They turned on the calming twinkly lights that were installed in the ceiling for just this

purpose, and then literally blew bubbles across my field of vision. I was indeed calmed, and for long

enough to get the scan. These people were angels and I am still floored recalling their kindness and

acceptance.

Buoyed, I was gingerly moved back to the wheelchair and steered out to the hallway to wait for the

orderly. When he eventually picked me up he had the same conversation with himself on the way

back as he had on the way there. What a relief to return to my family and have some more lukewarm

tea on my hard hospital bed. What a relief to be immobile once again. At this point being alive was

terribly exhausting.

After all that I reached the familiar milestone of being told by the nurses that I had to be able to pee

independently to leave the hospital and they’d be taking out the catheter to see if I could do it. Based on

my first time around I told them there was no way in hell I would walk to the bathroom until I was

done with the IV pole. They relented, and one or two drip bags later my time eventually came. Of

course with the shared room comes the joys of the shared bathroom. I gingerly shuffled in there and sat

on the toilet, which the nurse had lined with the carboard “pee hat” urine catcher to prove I could do it.

While trying to coax urine out of my flattened urethra the grandma from the other family walked in on

me in all my indignity. She gave me a sheepish smile, bowed, and backed out of the room, her son

chastizing her for ignoring the “patients only” sign just so she could get a glass of water or wash her

thermos or something. They apologized sincerely and brought us cinnamon buns from Solly’s.

Though I truly wanted to leave after two days, it was clear I needed to stay for at least 3. We endured a

terrible night nurse and got the day nurse to give us a talented and compassionate substitute for our

final evening. I repeated the cycle of weeping, bleeding, waking repeatedly, nursing the newborn,

taking medication, taking more medication, eating weird food, possibly sleeping, seeing some visitors,

and eventually peeing a couple more times. Don’t get me wrong, there were lots of good times.

Watching and getting to know my newest little love certainly diminished the pain I felt with every

movement, the fear of coughing, the utter helplessness and inability to fend for myself. Amazingly

Alice’s early cries were that of “la” and she assertively sang her way through the entire stay.

I did eventually get to go home. With my parents present to hold the child and help me stand we

carefully packed up our bags one strewn piece at a time and convinced the nurse we knew how to

buckle an infant car seat. Armed with Naproxen and all the extra absorbent material I could grab from

the hospital I returned home to an alienated toddler and helpful in-laws. My heart swelled with love and

pride for my precious infant, who was rapidly growing and blessedly healthy. I was proud of myself for

laboring so well and having made the best possible decisions with regard to my caregivers. But I was

still in pain.

As is the case after major surgery I was regularly overcome with fatigue and simple tasks became

monumental. Bending to pick items up off the floor was difficult. Picking up my older child, which he

desperately wanted, was ill-advised but I did it anyways when he cried at night, frightened about why

he had been separated from us so suddenly and for so long for the first time. I sweat, I bled, I hurt.

In between feeling awful, I did feel good, I did make progress. But every time I strained on the toilet my

body initiated memories of the hours of fruitless pushing and I doubted myself. I often wept at this

creeping feeling of inadequacy; I could not make sense of it. Why couldn’t my body do what it was

designed to do? Was I just not brave enough to endure the earth-shattering pains I felt in my hip before

changing the plan and leaving for the hospital? Was there some error on the part of my caregivers?

Shouldn’t somebody have had some brilliant idea, like using a Rebozo or something, that would have

turned the infant and save the day? I may never know the answer to these questions, and probably

nothing anyone could tell me would change my feelings. None of this could change what happened, yet

the memory of the body persists. What truth was I really searching for?

Entering the mystery, embracing the journey. To give birth to my children I walked an ancient passage,

one trod by all humans on this earth that ever came before me. The responsibility of bringing dark into

light, fruit to the harvest, offering embodiment to sacred life. The sacrament. As I lived the experiences

of my predecessors, my body ran a biological program. Every cell knew what was supposed to happen.

Body and mind working together towards that common goal. Affirmation, confidence, surety.

And yet I was unable to give birth naturally. In the end, my biological programming did not match with

my lived experience, and so my woman-self was fractured, cellular consciousness and memory at odds:

this is the truth I brought to light for myself.

In having a second cesarean, the scar tissue of the first is literally carved away. You do not get two

notches on your belt to show the world. Instead risk factors on your chart go up should you wish to

accumulate more children, and you live with the knowledge that your guts have been known more

intimately by others than by yourself. You may envy the percieved success of other women who had

their babies naturally, who got them out at home or at the hospital, whose caregivers thoughtfully did

some magic trick to get the baby to cooperate with its host. Those women may talk about their dreams

of another child, and thoughtlessly ask you about yours. You may see them frown in fear and disgust if

you try to discuss your uterine tear, your blood loss, your revulsion at what you heard and felt while on

the operating table. You may hear them compare your birth experience to their own, analyzing at what

point the circumstances diverged to ensure their success and your implied failure. You may see them

find it too painful to listen to you explain your decision not to endanger your uterus or endure surgery

again, opting to forego having another child even though you thought you wanted one.

Still more well-meaning people will tell you to be thankful for your healthy child (of course you are).

To be thankful for Western medicine (of course you are). To be thankful you could have another child if

you really wanted (of course you are). To be thankful your situation wasn’t worse (of course you are).

To acknowledge that you aren’t the only birthing woman who was unsatisfied with the way the process

turned out (of course not). To acknowledge that you aren’t the only birthing woman who was hurt in

some way, physically or spiritually, and that in comparison others would envy you.

While all that may be true, don’t listen, for these people are not listening to you. If they were, they

would first acknowledge that the truth they seek in comparing circumstances exists side by side with

your pain, and that neither is privileged above nor answer to the other. Such comparative truths are not

to be used as a balm for your spiritual wounds, as this kind of treatment will be ineffective at best. Do

allow room in yourself to acknowledge the fact that we can be simultaneously grateful and hurt.

Embody it. Live it.

And as you live your truth, ask yourself what made you feel powerful during your experience. For me,

it was choosing to try for a VBAC. Choosing a midwifery team whose rigorous training was anchored

by their breadth of experience and commitment to informed consent. Choosing to labour at home and

be cared for by skilled and loving women who respected me. Experiencing my body’s feral wisdom as I

dilated and felt the first touch of my baby outside the womb. Being treated with respect when I arrived

at the hospital. Knowing that I gave my baby the best possible chance for an optimal birth. Ensuring

that, despite the surgery, my infant received as much cord blood and vaginal bacteria as was possible

given the circumstances. Knowing that I made the Best. Possible. Decision.

And so I ask you to witness my simultaneous feelings of failure and triumph. To see that my grief is as

tangible as my empowerment, and that they are inextricably linked. In writing this, I acknowledge my

feelings and do not judge them, for they simply are. I ask that you do the same, both for me and for any

other woman who cares to confide her experience in you. In that sacred space, there is healing.

Written By Emily Smith.

Thank you for sharing your beautiful story, Emily. If you are looking for more birth stories check out this caesarean breech birth story.

Morag Hastings is a Doula and Birth Photographer located in Vancouver, BC Canada. Come check out more of her work on her facebook page at www.fb.com/vancouverbirthdoula or feel free to email me at moraghastings@gmail.com I would love to hear from you.